2. Jupyter Notebooks¶

This notebook demonstrates some features on Jupyter we will be using throughout the course.

A Jupyter notebook is a web-based environment for interactive computing. You can work in this environment interactively just as you would using the Jupyter shell. In addition, you can also store and run programs in an Jupyter notebook just like you would from the Spyder editor window. Thus, it would seem that an Jupyter notebook and the Spyder do essentially the same thing. Up to a point, that is true. In the final analysis, however, Spyder (or some similar Python development environment) is generally more useful for developing, storing, and running code. An Jupyter Notebook, on the other hand, is excellent for logging your work in Python. That is why we suggest using them for homework assignments. You may find them useful in other contexts as well.

2.1. Launching an Jupyter notebook¶

To create an Jupyter notebook, launch a powershell or bash terminal and activate the numeric environment:

conda activate numeric

At the prompt, type

jupyter notebook

This will launch the Jupyter notebook web application and will display the dashboard page.

To create a new python notebook, pull down the new menu and select Python3. That will open a new with the provisional title Untitled. in a new tab in your browser. To give the notebook a more meaningful name, pulldown the File menu and rename your notebook to FirstNotebook. That file will contain all the work you do in the Jupyter notebook. Next time you launch Jupyter Notebook from this same directory, all the Jupyter notebooks in that directory will appear in a list on the Jupyter

Notebook Dashboard. Clicking on one of them will launch that notebook.

2.2. Using an Jupyter Notebook¶

When you open a new Jupyter Notebook, an Jupyter interactive cell with the prompt In[ ]: to the left, appears. You can type code into this cell just as you would in the Jupyter shell. For example, typing 2+3 into the cell and pressing Shift-Enter (or Shift-Return) to execute the cell yields the expected result. Try it out.

[1]:

import numpy as np

from matplotlib import pyplot as plt

np.sin(np.pi / 6)

[1]:

0.49999999999999994

Below the result a new Jupyter interactive cell appears ready for your next entry. The commands in the cell above are separated by the Shift (without Enter or Return) so that they appear in the same cell. They are then both executed by pressing Shift-Enter (or Shift-Return). After importing numpy, typing sin(np.pi/6.) and pressing Shift-Enter produces the expected result (to nearly 1 part in \(10^{16}\)).

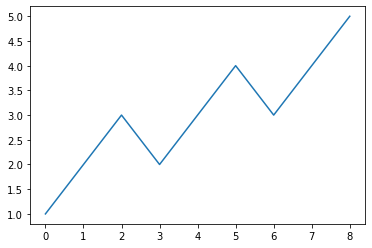

You can also create plots in an Jupyter notebook. For example, typing plt.plot([1,2,3,2,3,4,3,4,5]) and pressing Shift-Enter produces the following. Note the semicolon at the end of the line suppresses output on the last line, as with matlab.

[2]:

plt.plot([1,2,3,2,3,4,3,4,5]);

Be sure to press the Save and Checkpoint icon at the far left near the top of the Jupyter Notebook window from time to time to save your work.

2.3. Running programs in an Jupyter Notebook¶

You can also run programs in an Jupyter notebook. As an example, we run the program introduced in the section on screenoutput. The program is input into a single notebook cell and then executed by pressing Shift-Enter.

[3]:

# Calculates time, gallons of gas used, and cost of gasoline for

# a trip. Set interactive=True to run

interactive=False

if interactive:

distance = input("\ninput distance of trip in kms\n")

else:

distance = 400.

distance = float(distance)

km_per_liter = 30. # kms per liter

speed = 60. # average speed (km/hour)

costPerLiter = 4.10 # price of gas in $/liter

#

time = distance/speed

liters = distance/km_per_liter

cost = liters*costPerLiter

print(f"\nDistance traveled = {distance:0.1f} kms")

print(f"\nDuration of trip = {time:0.1f} hours")

print(f"Gasoline used = {liters:0.1f} liters (@ {km_per_liter:0.0f} km/liter)")

print(f"Cost of gasoline = ${cost:0.2f} (@ ${costPerLiter:0.2f}/litre)")

Distance traveled = 400.0 kms

Duration of trip = 6.7 hours

Gasoline used = 13.3 liters (@ 30 km/liter)

Cost of gasoline = $54.67 (@ $4.10/litre)

In this example, the program requests input from the user: the distance of the trip. The program runs up to the point where it needs input from the user, and then pauses until the user responds and presses the Enter or Return key. The program then completes its execution. Thus the Jupyter notebook provides a complete log of the session.

2.4. Annotating an Jupyter Notebook¶

An Jupyter notebook will be more easily comprehended if it includes annotations of the session. In addition to logging the inputs and outputs of computations, Jupyter Notebook allows the user to embed headings, explanatory notes, mathematics, and images.

Suppose, for example, that we want to have a title at the top of the Jupyter notebook we have been working with, and we want to include the name of the author of the session. As an example, open the Insert menu near the top center of the window and click on Insert Cell Above, which opens up a new input cell above the current cell cell. Next, we click on the box in the Toolbar that says Code. A list of cell types appears: Code (currently checked), Markdown, Raw NBConvert,

Heading. Select Heading; immediately the In [ ]: prompt disappears, indicating that this box is no longer meant for inputing and executing Python code. Type “Demo of Jupyter Notebook” and press Shift-Enter (or Shift-Return). A heading in large print appears. Once again, select the Insert menu and click on Insert Cell Above. Again, click on the Toolbar that says Code, but this time select Heading and use two ## hashes. Type your name into the newly

created cell and press Shift-Enter. Your name is printed in the cell in slightly smaller print than for the previous case.

You can also write comments, including mathematical expressions, into an Jupyter Notebook cell. Let’s include a comment after the program we ran that calculated the cost of gasoline for a road trip. First we place the cursor in the open formula cell below program we ran and then click on the box in the Toolbar that says Code and change it to Markdown. Returning to the cell, we enter the text of our comment. We can enter any text we wish, including mathematical expressions using the

markup language Latex. (If you do not already know Latex, you can get a brief introduction at these sites: http://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/LaTeX/Mathematics or http://ctan.forsale.plus/info/short-math-guide/short-math-guide.pdf) Here we enter the following text:

The total distance \(x\) traveled during a trip can be obtained by integrating the velocity \(v(t)\) over the duration \(T\) of the trip:

\begin{align} x = \int_0^T v(t)\, dt \end{align}

After entering the text, pressing Shift-Enter.

The $ symbol brackets inline mathematical expressions in Latex, while the \begin{align} and \end{align} expressions bracket displayed expressions. You only need to use Latex if you want to have fancy mathematical expressions in your notes. Otherwise, they are not necessary.

Suppose you were importing a data (.txt) file from your drive and you wanted to print it out in one of the notebook cells. If you were in the terminal, you could write the contents of any text file using the command cat filename (Mac) or type filename (PC). You can execute the same operation from the Jupyter prompt using the Unix (Mac) or DOS (PC) command preceded by an exclamation point.

2.5. Editing and rerunning a notebook¶

In working with an Jupyter notebook, you may find that you want to move some cells around, or delete some cells, or simply change some cells. All of these tasks are possible. You can cut and paste cells, as in a normal document editor, using the Edit menu. You can also freely edit cells and re-execute them by pressing Shift-Enter. Sometimes you may find that you would like to re-execute the entire notebook afresh. You can do this by going to the Kernel menu and selecting Restart.

A warning message will appear asking you if you really want to restart. Answer in the affirmative. Then open the Cell menu and select Run All, which will re-execute the notebook starting with the first cell. You will have to re-enter any screen input requested by the notebook scripts.

2.6. Quitting an Jupyter notebook¶

It goes almost without saying that before quitting an Jupyter notebook, you should make sure you have saved the notebook by pressing the Save and Checkpoint item in the File menu or its icon in the Toolbar.

When you are ready to quit working with a notebook, click on the Close and halt item in the File menu. Your notebook browser tab will close and you will return to the Jupyter Notebook Dashboard. Just close the Jupyter Notebook Dashboard tab in your browser to end the session.

Finally, return to the Terminal or Command Prompt application, hold down the control key and press c twice in rapid succession. This stops the Jupyter Notebook session. You should see the normal system prompt. You can then close the Terminal (Mac) or Command Prompt (PC) session if you wish.

2.7. Working with an existing Jupyter notebook¶

To work with an existing Jupyter notebook, open the Terminal and navigate to the directory in which the notebook you want to work with resides. Recall that Jupyter notebooks have the .ipynb extension. Launch the Jupyter Notebook Dashboard as you did previously by issuing the command

jupyter notebook

This will open the Jupyter Notebook Dashboard in your web browser, where you should see a list of all the Jupyter notebooks in that directory (folder). Click on the name of the notebook you want to open. It will appear in a new tab on your web browser as before.

Note that while all the input and output from the previous saved session is present, none of it has been run. That means that none of the variables or other objects has been defined in this new session. To initialize all the objects in the file, you must rerun the file. To rerun the file, press the Cell menu and select Run All, which will re-execute all the cells. You will have to re-enter any screen input requested by the notebook scripts. Now you are ready to pick up where you left off

the last time.

[ ]: