Table of Contents

1 00 - Introduction

1.1 First steps

1.1.1 Installing python

1.1.2 Installing extra dependencies

1.2 Course objectives

1.3 Motivation (editorial)

1.3.1 Concurrency vs. parallelism

1.3.2 Threads and processes

1.3.3 Thread scheduling

1.3.4 Releasing the GIL

from IPython.display import Image

00 - Introduction¶

First steps¶

(Note – this material is under construction and might change significantly between now and June 14)

Installing python¶

All the code used in the tutorial can be run on a Windows, Mac, or Linux laptop

We will use a python distribution called Anaconda to run a series of Jupyter notebooks (you are reading a jupyter notebook now).

You’re definitely encouraged to bring your laptop to the tutorial, please do the following:

Download and install Miniconda 3.6 from https://conda.io/miniconda.html on your laptop, accepting all the defaults for the install (I specified an install into a folder named ma36 below):

If you are running on Windows:

Press the ⊞ Win key to open a cmd shell and type: anaconda prompt

This should launch a cmd shell that we can use to install other packages

To test your installation, type

conda list

at the prompt, which should show you a list of installed packages starting with:

(base) C:\Users\paust>conda list # packages in environment at C:\Users\paust\ma36:

If you are running MacOS or Linux, after the install launch a bash terminal. Hopefully when you type:

conda list

you will see output that looks like:

% conda list # packages in environment at /Users/phil/mb36: # # Name Version Build Channel

Installing extra dependencies¶

To install the software required to run the notebooks:

Download conda_packages.txt by right-clicking on the link.

From you cmd or bash terminal, cd to the folder containing that file and do:

conda install --file conda_packages.txt

If this succeeds, then typing the command:

python -c 'import numpy;print(numpy.__version__)'

should print:

1.14.2

(or possibly a higher version)

If you have trouble with these steps, send me a bug report at paustin@eos.ubc.ca and we can iterate.

Course objectives¶

- The objective is to learn how to write shared-memory Python programs that make use of multiple cores on a single node. The tutorial will introduce several python modules that schedule operations and manage data to simplify multiprocessing with Python.

- Benchmarking parallel code

- Understanding the global interpreter lock (GIL)

- Multiprocessing and multithreading with joblib

- Checkpointing/restarting multiprocessor jobs

- Multithreaded file i/o with zarr and parquet

- Writing extensions that release the GIL:

- Using numba

- Using C++ with cffi

- Using dask/xarray to analyze out-of-core datasets

- Visualizing parallelization with dask

- Setting up a conda-forge environment for parallel computing

Motivation (editorial)¶

- I learned this material by cargo culting, but my hope is that this set of working examples can shorten the learning curve for newcomers trying to combine Python with C++/C/ Fortran. Multiprocessing, multithreading and cross language programming are all in a state of rapid development; these constant changes make it impossible to google a definitive answer about any of these topics.

- I’m presenting my personal opinion about the best way to organize

mixed language computer programs so that they:

- Give the same answers each time they are built and run

- Can be easily shared with colleagues, including yourself six months in the future.

- Save time (your time + collaborators’ time + machine time).

- I’ll maintain this repository, and test it on Linux, OSX and Windows. If you hit bugs, I welcome github issues and pull requests, or an emailed questions/examples of problems.

- This is an area of Python programming that is changing/developing on an almost weekly basis. There’s reason to believe that things (meaning the way that we build and deploy multi-language applications) will stabilize over the next year or so.

Concurrency vs. parallelism¶

Threads and processes¶

From Wikipedia:

“In computer science, a thread of execution is the smallest sequence of programmed instructions that can be managed independently by a scheduler, which is typically a part of the operating system.[1] The implementation of threads and processes differs between operating systems, but in most cases a thread is a component of a process. Multiple threads can exist within one process, executing concurrently and sharing resources such as memory, while different processes do not share these resources. In particular, the threads of a process share its executable code and the values of its variables at any given time.”

Threads and processes in Python¶

Reference: Thomas Moreau and Olivier Griesel, PyParis 2017 [Mor2017]

Python global intepreter lock¶

- Motivation: python objects (lists, dicts, sets, etc.) manage their own memory by storing a counter that keeps track of how many copies of an object are in use. Memory is reclaimed when that counter goes to zero.

- Having a globally available reference count makes it simple for Python extensions to create, modify and share python objects.

- To avoid memory corruption, a python process will only allow 1 thread at any given moment to run python code. Any thread that wants to access python objects in that process needs to acquire the global interpreter lock (GIL).

- A python extension written in C, C++ or numba is free to release the GIL, provided it doesn’t create, destroy or modify any python objects. For example: numpy, pandas, scipy.ndimage, scipy.integrate.quadrature all release the GIL

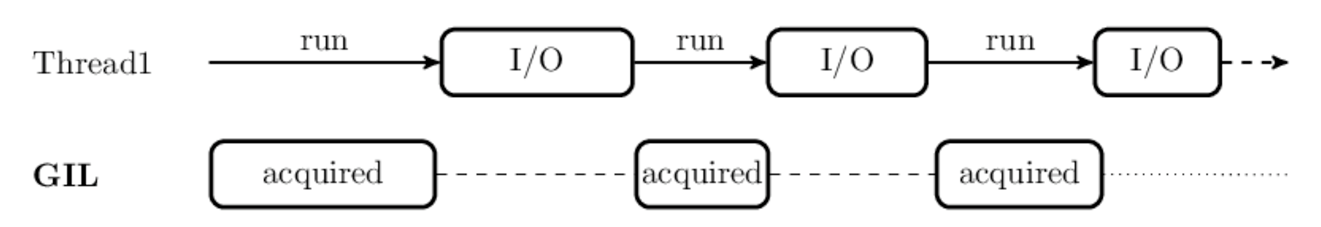

- Many python standard library input/output routines (file reading, networking) also release the GIL

- On the other hand: hdf5, and therefore h5py and netCDF4, don’t release the GIL and are single threaded.

- Python comes with many libraries to manage both processes and threads.

Thread scheduling¶

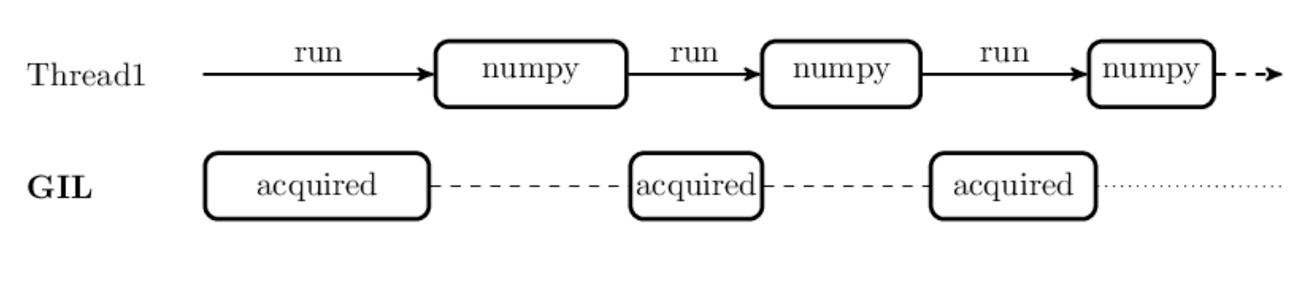

If multiple threads are present in a python process, the python intepreter releases the GIL at specified intervals (5 miliseconds default) to allow them to execute:

Image(filename='images/morreau1.png') #[Mor2017]

Note that these three threads are taking turns, resulting in a computation that runs slightly slower (because of overhead) than running on a single thread¶

Releasing the GIL¶

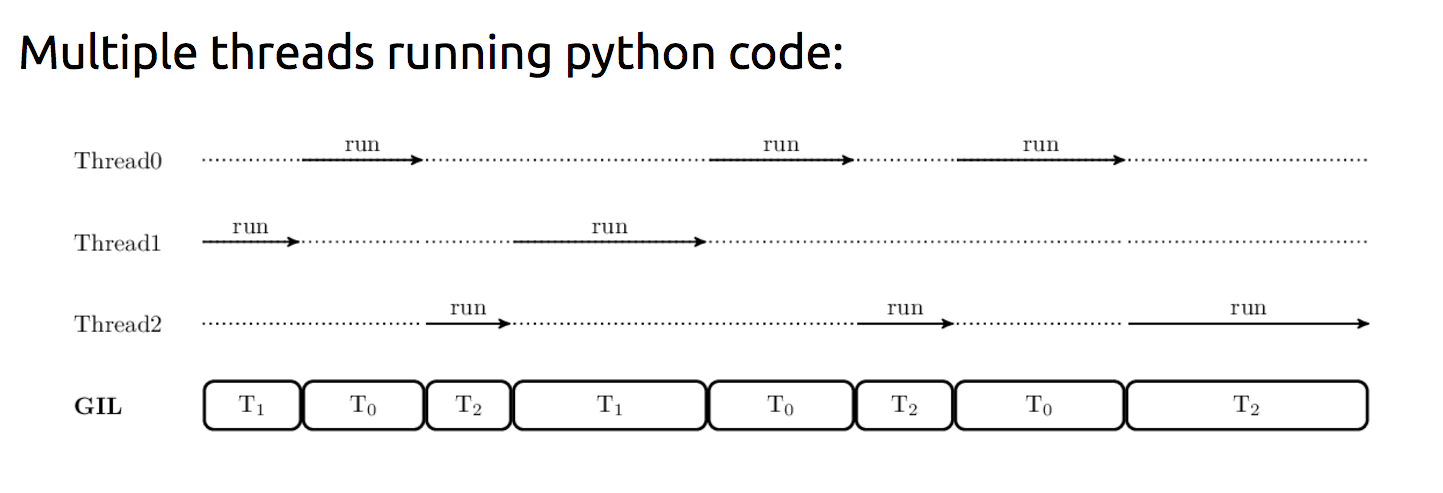

If the computation running on the thread has released the GIL, then it can run independently of other threads in the process. Execution of these threads are scheduled by the operating system along with all the other threads and processes on the system.

In particular, basic computation functions in Numpy, like (_*add_* (+), _subtract_ (-) etc. release the GIL, as well as universal math functions like cos, sin etc.

Image(filename='images/morreau2.png') #[Morr2017]

Image(filename='images/morreau3.png') #[Morr2017]